© 2019 by Peter Kratz. Jede Verwendung des

Textes

und

der Abbildungen unterliegt dem Urheberrecht.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

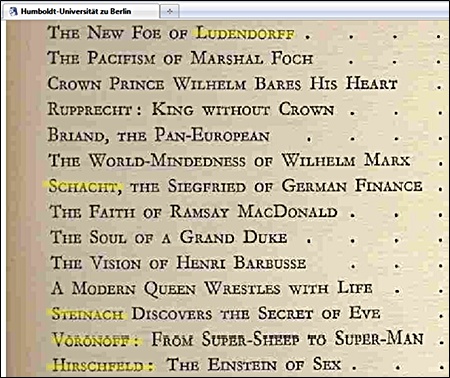

The

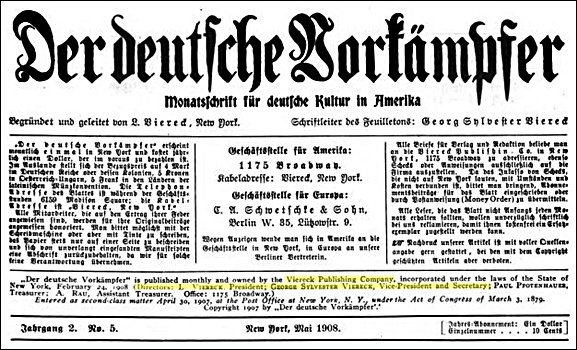

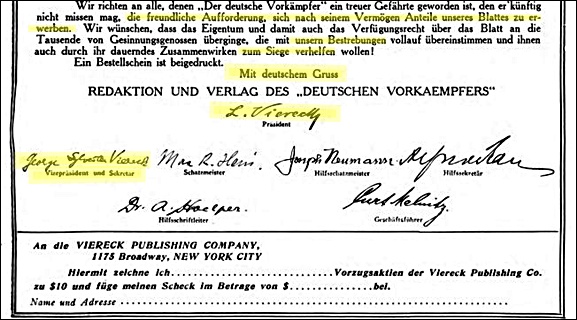

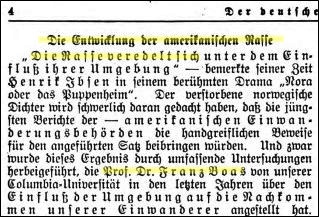

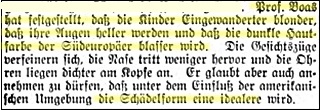

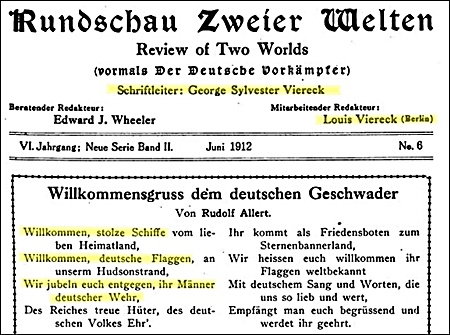

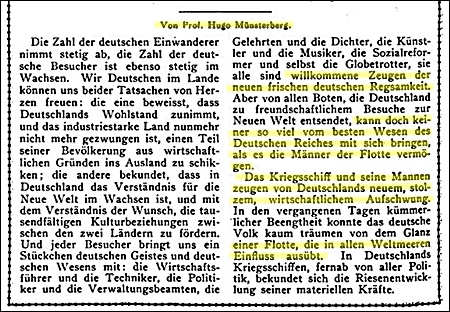

ultimate Hirschfeld revelation:

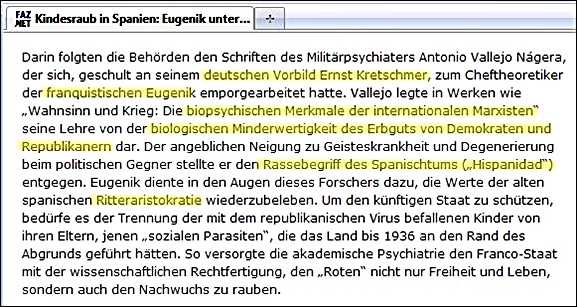

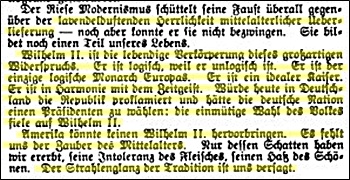

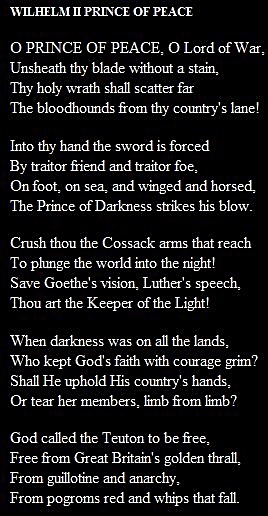

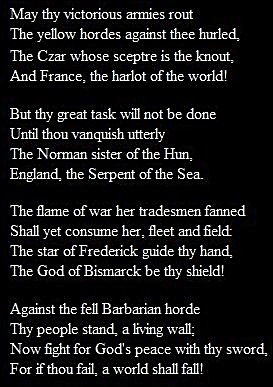

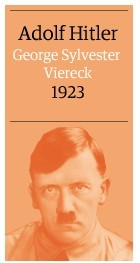

Magnus Hirschfeld: Nazis Paved His Way When the well-known “sexologist” traveled to the US in 1930-31, his trip was organized by right-wing German chauvinists. BIFFF... has discovered that a quote from a letter allegedly written by Hirschfeld, which was printed in a book by today's well known German Sexologist Volkmar Sigusch, is wrong. The truth: Hirschfeld sought to create a rigid, authoritarian “formed” society. The terrible truth: We are the first ones to discover the similarities between the Protocols of the Wannsee Conference and the quotes from Hirschfeld's five volumes book "Geschlechtskunde" (Sexual Knowledge) found in Sigusch's work. BIFFF... has analyzed the writings of the Nazi George Sylvester Viereck, a friend of Hirschfeld. Our analysis shows that what Hirschfeld-apologists call his “Jewish messianism” actually came from the Conservative-Revolutionary (i.e. "Alt-Right") ideas of the Pan-Germanic Viereck and his father, both lifelong friends of Hirschfeld. The German-American G. S. Viereck is still an object of hate in the United States today because of his support for the Kaiser and then Nazi Germany during the World Wars. This is not the first time that there has been a German national hero whose right-wing extremist ideology is ignored or played down. And that's for sure: Graf Stauffenberg was of course the deeper rogue, a perpetrator of the war of extermination. For almost five years this army officer backed the crimes of the Nazi army; for three years he was part of the “campaign against the Jewish-Bolshevist system” for the “atonement of the Jewish Untermensch” in Eastern Europe, as Wehrmacht generals put it at the time. In WW II, the war of extermination, he covered SS-murderers' asses – with full enthusiasm for war against the Polish “mob,” against the Polish “Jews” and against the East European “mixed people” (as he himself called them), and also out of German chauvinism and military obedience. He admitted that he was anti-Semitic – and despite all this he is honored every year by German heads of state from all parties – despite the fact that he was an insurgent only in the last hours, after everything that he as a soldier of Hitler's Wehrmacht had tried to achieve in the war was already lost, an insurgent only after huge numbers of Jews and Roma had been killed in a biological delusion in the name of his “holy Germany”. In contrast, Hirschfeld hated anti-Semites. By the beginning of the 1920s he had already been a victim of their violent acts, and even earlier he was victim of their more subtle agitations. During the terrors of 1932 - 1933 he couldn't return to his home in Germany out of fear for his life. The anti-Semites made Hirschfeld, who came from a Jewish family, into a "Jew", an identity he himself - who was a Nietzscheanist and a follower of the social Darwinist Ernst Haeckel and member of Haeckel's pantheistic evolutionary-biologistic cult "Monistenbund" - did not want. He did not get a chance to make a stand against the Nazis in power, and he was too soft for this task, too effeminate, a fairy, which is why he is loved today by not a few followers. And his weakness is not the worst reason to love him. It's a piece of humanity amidst his contempt for the “biologically unworthy”, defined as "disabled persons", whose physical existence he too wanted to eliminate using politics. Now the German state is honoring him. They have established a foundation which is supposed to serve as collective reparations for the persecution of homosexuals in Nazi Germany (and also, though this is admitted not until the year 2017, in Adenauer's Germany). This foundation received his name. Is he a man worth honoring? It is impossible to reconcile the inconsistencies within Hirschfeld. Should one? Should one try? He broadly concealed his own homosexuality until the middle of the 1920s. Even close co-workers like the psychologist Arthur Kronfeld, with whom he operated a medical practice at the Institute for Sexology starting in 1919, knew nothing of his sexuality. Hirschfeld thought that homosexuals were “degenerated," and had bad, sick genes that he wanted to “weed out” through eugenics – what did he think about himself? He justified his support for the legalization of homosexual relationships between men by saying that the ban would make sexually desperate homosexual men enter into heterosexual marriages, where they would pass on their bad genes and biologically perpetuate the traditions of “degenerating families.” This idea shows just how far Hirschfeld was from any goal of sexual emancipation, any recognition that a free sexual life is a human right. Hirschfeld, who came from a Jewish family, was affiliated with the neo-pagan nature-oriented “Monism” religion, in which intellectual "Germanics" rubbed elbows with Social Darwinists. He was an avowed fan of the monist founder Ernst Haeckel and joined his Monistic Society ("Monistenbund"). A direct path leads from the intellectual beliefs of the sect to Nazism and its crimes. Many of its participants let themselves be part of the “Gleichschaltung,” the consolidation of Nazi power, before their religion was outlawed. Haeckel himself, as a “philosopher,” agitated against the idea of equality and that “Judeo-Christianity” should be the foundation of the ideas of a civilized society. He was posthumously accepted by the Nazis as one of their own, as an early proponent of the idea of “lower races.” Hirschfeld's Jewish background was not known for a long time by many of his extreme right-wing colleagues in “sexology,” a new discipline of psychology and medicine that began as an attempt to further the "German warrier race" through racial cleansing and eugenics. Sexology was founded by those who wished to weed out everyone who didn't meet the romantic ideal of a warrior, and Hirschfeld, who was not a scientist but “only” a private physician for general medicine, who kept his secrets of being gay and an offspring of a Jewish family well, a “sissy,” cozied up to them in order to gain recognition. Hirschfeld, who greeted the outbreak of World War I with excitement, saw sexuality as a means to further the "German race" as competitions between different peoples broke out, in a time when a division between sexuality and reproduction was unthinkable. Did he himself have fun having sex? He never wrote out the answer to this question, despite his many writings, which today are poured over by so many of his followers. But he did write again and again about his belief that the main goal of sexuality was a biologically strong people. For example in the foreword to his "Weltreise"-book ("World Journey") in 1933 he wrote that sexology, as he practiced it, should make possible the “selection” of people, “the purposeful preference of hereditary factors that are beneficial for the bodily health and mental aptitude of posterity, and on the other hand, by shutting out undesirable characteristics.” No one yet knew anything of gender theory, any idea about the right of sexual self-determination would have conflicted with “marital duties,” and the suggestion of adjusting criminal law regarding the right of sexual self-determination would have met only derision. Cultural relativism had not yet entered into the definitions of health and soundness; anyone who was “disabled” should just vanish. Hirschfeld seemed to have a clear idea of which people were “worthy” and which were “unworthy.” Worthy for whom? For themselves, for capitalism, for Kaiser or Führer? Or perhaps “for the graves, Mother, for the Graves,” as Kurt Tucholsky's anti-war song from the 1920s answered why mothers bore and raised their children. Hirschfeld remained silent on the question of “worth for whom.” He left the decision to others, including the Nazis. “By producing better and happier people, eugenics aims to create a better and happier humanity. Ultimately sexual ethnography and this, a book dedicated to it, also serve this aim,” he wrote in 1933 at the close of the foreword to his book "Weltreise eines Sexualforschers im Jahre 1931/32" (World Journeys of a Sexologist in The Year 1931/32), his best known work. It seems that he knew who was “good” and who “better,” even who was “happy.” He wanted to define these things, offering him an authoritarian and rigid position that seemed to be a backbone for this “sissy” in the turbulences of the world wide economic crisis. His delusional hope was the “new human kind,” who the Social Darwinists, who saw themselves as gods, wanted to create. The delusions of the world leader Magnus

Hirschfeld:

The end of the foreword from Hirschfeld's book "Die Weltreise eines Sexualforschers". At the beginning of the 1980s, a Hirschfeld Renaissance began in West Germany. This was surprising after the movement of " '68" criticized the continuence of Nazi traditions in Adenauer's Germany, after the sexual revolution that finally discovered the idea of sex being fun as a social phenomenon, and after the proclamations of revulsion against any sort of human selection (which had as its very goal the possibility of the targeted selection of foreign workers, preferably ones without any sort of sexual needs!). Why Hirschfeld, who wanted to select superior people? In 1985 the German weekly magazine Der Spiegel published an article by sexual researcher Volkmar Sigusch. This article introduced to a wide public for the first time, if still in a very restrained manner, the idea of Hirschfeld as a biological determinist and eugenicist who did not condemn the 1933 “Hitler Experiments” on people who were “unworthy for life,” but called for waiting before passing judgment on them (Sigusch, quoting Hirschfeld). Sigusch criticized this and the “New Person”/"New Humanity"-ideology of the whole group of German sexual researchers who in the first thirty years of the 20th century had dreamed of breeding those they deemed “worthy of life” and killing those who were “unworthy of life.” They justified this as being in the service of a higher purpose, which aligned as nicely with the goals of war and capitalism and the deconstruction of social services and health insurance as the Pan-Germanic romanticism served the Kaiser and Führer. Sigusch's article also questioned Hirschfeld's praise of “war craft” as “artwork” at the beginning of World War I, and quoted from Hirschfeld's 1915 tract celebrating the outbreak of war, “Why Do People Hate Us? A Reflection on the Psychology of War,” in which Hirshfeld wrote: “As the deployment of our troops in August 1914 brought the sleeping power of our people's army to life, we felt – to quote Goethe - 'How everything weaves itself into the whole, One in the other works and lives!'” Sigusch criticized the beginnings of the naive Hirschfeld-Renaissance, that wanted to remain silent about the “racial cleansers” and eugenicists that paved the way for Nazi crimes under the guise of Hirschfeld's “sexual reforms.” Excursus: Volkmar Sigusch, Evangelist of the Hirschfeld Religion At the time of his Spiegel article, Sigusch knew only fragments about Hirschfeld's life, and couldn't see the big picture: Hirschfeld's work as a logical part of the build-up to the Nazi crimes. He just wanted to further polish the legacy of Hirschfeld, the founder of the "Institut für Sexualwissenschaft" (IfSw, Institute for Sexology or Institute for Sex Research) in Berlin, as a shining model of sexual emancipation, which he had never been. It was not until our 2003 investigation of the members of the IfSw that the facts about the circle of people around Hirschfeld came out. In that investigation we showed that many of Hirschfeld's colleagues and close coworkers longed for and praised the First World War, and even in 1917, after other war mongers had long renounced their praise, still called the youth of Europe to follow the Kaiser Wilhelm II as their leader. These were the people with whom Hirschfeld ran the "Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee" (WhK, "Scientific Humanitarian Committee") starting in 1899, and the people with whom he founded and ran the IfSw in 1919, five years after his praise for the war. Not today's Hirschfeld apologists ever did this research on the politics and sexual politics of the Hirschfeld group in the early 20th century, but BIFFF… did and still does. Sigusch's failure to adequately categorize and criticize a “sexology” that arose out of a legacy of eugenics and racial cleaning ("Rassenhygiene"), whose goal was not sexual emancipation but rather a selective breeding of a people, stems from the fact that he did not have an understanding of anti-fascist thought, and was not familiar with the anti-fascist understanding of society, although he claimed to be a follower of Adorno. In order to understand the responsibility that (and how) the biological-medical “sexual sciences” bore for the crimes of fascism, one must first fully understand the way that different forms of intellectual fascism developed, and how practically-applied tenants of Fascism and its crimes developed in turn from these seemingly harmless intellectual currents. One must also understand how necessary anti-fascist thought is to a critique of Stalinist eugenics. And such knowledge is also necessary in order to understand Hirschfeld's friendship with Nazis, the work of Nazi race theorists at the IfSw, and Hirschfeld's deference to Nazi health politics. More careful research shows that there is a clear lineage in Hirschfeld's work and behavior that is in no way contradictory or inconsistent, despite the desire of current Hirschfeld apologists to obscure his obvious culpability in Nazi crimes. Since his initial article Sigusch has distanced himself from his earlier critique of Hirschfeld, claiming that it is misunderstood, and has accused others of having turned against sexology. He did so vehemently in his 2008 book "Geschichte der Sexualwissenschaft" (History of Sexology), a popular science text that – although it is painful to say given Sigusch's many services to the emancipation movement – is largely trash. An even better-known example is his most recent interview with Der Spiegel, in which he offers a view into his own psyche – a lonely, deeply disappointed, threatened-feeling man whose life's work was destroyed by the conservatives. (“König Sex,” in Der Spiegel Nr. 9/2011) Sigusch was always half naive and half vaguely on the left, and today his naiveté has fully overpowered him. With his pronouncement in the Spiegel interview that sexual fantasies always have to be dirty, and that cleanliness, conscience, and rationality are poison to eroticism, he continued on the path that he had traveled for 30 years: away from civilization, back to the law of the jungle. The person is seen as an animal and should be allowed to remain that way, and his bedroom supposedly offers him a free place to be that way. This ignores that society follows human, not animal rules, and that even the erotic realm is planned along rational profit-driven principles of “marital hygiene,” through the consumption of commercial and pay-per-view TV, porn and sex-toys. The bedroom is not a place of freedom, but in actuality is just another place where - through the curtain - the constraints of the sexual-industrial complex rule, because Adorno's imagined “enclaves of immediacy” remain nothing but make-believe. “Dirtiness” has long been transformed into a commodity, the freedom fight of the formerly ostracized has now been reclaimed: see the German television broadcast "Wa(h)re Liebe" (“true love/love as ware) in which Ernie Reinhardt, alias Lilo Wanders, sold the capitalization of sexuality, disguised as exactly the same act of freedom as his participation in almost every CSD demonstration, to a wide audience. To be driven by the unknown – it was Sigmund Freud's horror. Sigusch has to admit that Freud, unlike Hirschfeld and his consorts, never spoke of those who were unworthy of love. But he has not admitted to it because eugenics is the law of the jungle, which seeks to replace the failure of natural selection in civilized society, it is the jungle in which cattle breeders who need suitable human material feel at home. This is in direct opposition to Freud, who wanted to free human individuals, who was not interested in consumers. Eugenics and the sex industry are two sides of the same coin, because in both human worth bows down to the logic of capitalist value realisation. Sexual researchers like Sigusch and Hirschfeld, who are rooted in pathological sexuality and who practice therapy as social control and domination, do not explain why they take sexuality out of civilization. Sigusch coined the phrase “normopath” for those whom he despises: the civilized people who follow the norms, whose opinions on sex are driven by a “toiletry-kit” mentality and thus destroy the “aura of mystery” that must be preserved in human relations (Sigusch). Against the rationality of capital, which still governs “behind the back,” unrecognized through the closed door of the bedroom, he, who was deeply affected and made insecure by his own failure as a liberator, sets -- the secret! The humble, unassuming, old secret. Sigusch became anti-enlightenment, not a critical enlightener like his teacher Adorno; an esoteric who exercised power in his therapy sessions with his secret knowledge. And so he belongs then with Hirschfeld, the know-it-all able to pass judgments on whose biology and psyche were worthy of life and whose were not. The conceited observer Hirschfeld, who advised lovers that it was better to divorce based on a questionaire about eugenics, and also made a killing on the side at the beginning of the sex industry by selling sex pills. It was an insight of critical theory that attempts to defend a primal area of freedom within prevailing circumstances must fail, because the attempt just further cements the existing circumstances. It is now clear that Sigusch never fully understood this idea: emancipation is not a one-way street. Emancipation requires the individual to seek to (self-) civilize the last formerly secret corners of his psyche, because 'there is no right life in the wrong one.' The dialectic of societal- and self-change may not be fully understood today, but “secrets” do not solve that problem. Even before Adorno many doctors knew that – the ones who closed themselves to the eugenics craze and insisted that they had sworn their oath to the wellness of individuals, not to a “higher” breeding of an anonymous people or class body. It is a lie that eugenics was fully embraced in the first half of the 20th century. This lie is propagated in modern Germany by Hirschfeld fans above all, in order to relieve their guilt. There were always alternative ethical actions by those who served human rights. Sigusch's portrayal of the IfSw in his history book is euphemistic to the point of making the reader sick. One would like to turn Sigusch's 1985 observation that Hirschfeld “at best [was] social and liberal” against its author. Sigusch is at best a Social Democrat of the middle, if not the “New Middle” of Germany's "red-green" utilitarian pro-capitalism Chancellor Gerhard Schröder! As if it were nothing, he writes sentence like “Here [in the IfSw] questions of eugenics such as 'suitability for marriage,' 'natural selection' and 'certificates of health' were discussed,” without even once asking the critical questions about these practices: suitable for marriage according to whose criteria? The criteria of the lovers themselves did not play a role for Hirschfeld, nor did love as a creteria, as his articles in the US press during his 1930-1931 trip to America showed. Sigusch's chapter on the IfSw mythologizes the Hirschfeld-Institute along the well known legends and is completely ignorant about the more recent research about the political and societal world view of the Institute. His personal profiles of Hirschfeld's coworkers are not only full of holes, but are marked by a complete lack of knowledge about the true background of their world views and politics. You only have to look at his portrait of Arthur Kronfeld, whom Sigusch discusses at great length but completely ignorantly (359). There is nothing about the idealogical foundation of Kronfeld's work and research, nothing about his reliance on the mythical German-chauvinist volks-philosophy of the anti-Semite 19th century philosopher Jacob Friedrich Fries. There is nothing about Kronfeld's later homophobic diatribes (which we published in 2012, when the Kronfeld papers entered into the public domain.) Sigusch merely repeats Ingo-Wolf Kittel's outdated portrayals of Kronfeld. Kittel is an Augsburg residented psychiatrist and the head of a “philosophical practice” for psychotherapy based on esoteric meditation techniques. He is credited for plucking Kronfeld out of obscurity by writing articles in “sexology” journals, but he doesn't understand anything about what Kronfeld thought and did. (Read allabout Kronfeld here on the BIFFF…-website!). Sigusch writes, in order to make Kronfeld seem more important, that he studied under the psychiatrist Karl Bonhoeffer after his time at the IfSw. But he does not explain that after that Bonhoeffer was among the euthanasia doctors of the Nazi regime, whose opinions cost people their lives. He doesn't explain that Kronfeld, in Moscow exile since 1936, participated in the Stalinist persecutions, disguised as psychiatry, as BIFFF... will soon document in a new investigation of Kronfeld's work. Without further comment, Sigusch introduces the anti-Semite and National Socialist Carl Müller-Braunschweig, who in 1933 was one of those responsible for the expulsion of Jewish psychoanalysts, as someone who “of course” was “allied with the IfSw and the things for which it stood” when the Institute was founded. Lonely Sigusch uncritically spouts the propaganda of the Hirschfeld apologists, attempting to curry their favor and looking for new allies. He offers them this: that the IfSw was a “sanctuary” for persecuted people – but Sigusch forgets to mention how Hirschfeld personally exploited needy young men, going so far as to use them for prostitution. In order to explain away Hirschfeld's cooperation as an expert witness during many prosecutions of sexual deviance in Berlin court proceedings, Sigusch says that he only participated “in order to reach a milder penalty or an acquittal.” (Hirschfeld apologists still remain utterly silent about this chapter in his life – they have never looked into the matter, although the transcripts of the trials are in archives in Berlin!) But take the case of Hirschfeld's evaluations of transvestites. He sought to enable them to change their gender on their identity papers. But this very process merely enables the smooth integration of deviants as cogs into the unquestioned machine. The people were supposed to seem ordinary when the police asked for their documents. But why, one would like to ask Sigusch and Hirschfeld, should a police officer at all check a “M” or “F” on a personal ID and then arrest those who are not wearing clothing that the officer finds suitable for their documented sex? Emancipation through blending in with oppression? Hirschfeld was not actually in pursuit of the civilizing or emancipation of (non-normative) sexuality during his court appearances, but actually sought its forced adherence to the categories of the Wilhelmine magistracy-society. Under the heading “Sanctuary” Sigusch presents, completely without criticism, the sentence: “The [IfSw] archive and Sex Museum presented perverse, fearful/lustful sexualia the way that a museum of natural history stuffs and displays exotic animals.” Aren't there any critical comments necessary here? But Sigusch thinks the opposite: the IfSw was “a, if not the center of the professionally-based and left-liberal motivated sexual reform movement during the Weimar Republic.” Hirschfeld, on the other hand, thought that homosexuals were “degenerating” carriers of bad, sick genes! Alpha and Omega:

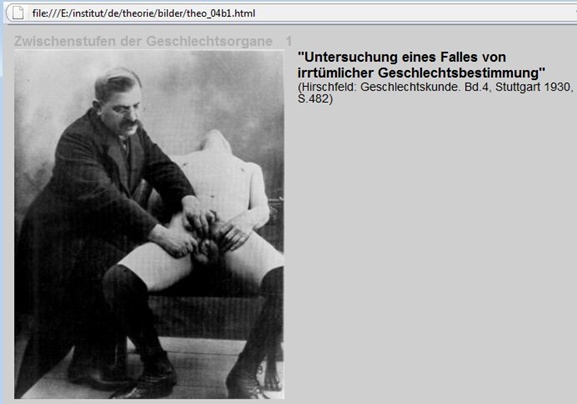

The person as materal, presented:

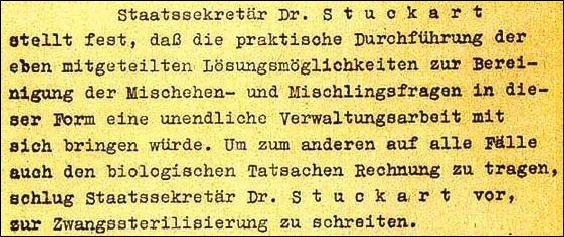

Useful? Not useful? For whom? For the person himself or for the drivers of the World Wars? A patient serves Hirschfeld (above left, the fumbler) to pompously draw attention to himself and his "Zwischenstufenlehre" (doctrine of intermediate stages). The Berlin-based Magnus Hirschfeld Society shows this picture without further comment on their online exhibit The Institute for Sexology (1919-1933). (BIFFF... screen shot from the CD edition.) The person, whose humanity was taken away by being an object of (special) treatment, presented by inhuman perpetrators:  Picture from Czewslaw Pilichowski: Es gibt keine Verjährung, Warsaw 1980; Archive of the main commission for the investigation of Nazi crimes in Poland. “Of personally integrity”?! On one hand, Sigusch's view of the connections between sexual science, eugenics and preparation for the Nazi crimes of extermination serves to wash Hirschfeld clean, although Sigusch has to admit that in “special cases” the IfSw spoke out in favor of “forced sterilization” (which Hirschfeld apologists have continually denied.) On the other hand it just shows Sigusch's naiveté again. Sigusch seriously states that Hirschfeld's role model August Forel, “like most sexual researchers, had personal integrity and only wanted the best for the sick and for all of human kind.” Then he turns around and in the same breath cites Forel's clamor for “forced sterilization of the defective subhuman (untermensch).” Is it possible to have “personal integrity” when one speaks, like Forel, about a “defective subhuman (untermensch)?” Sigusch trivializes Forel's detractors: “His book Die sexuelle Frage (The Sexual Question), which was published first in 1905, went through many editions and was translated into many languages. The watchword of his book, and the entire era, was: betterment of 'human material,' extermination of useless and unfit people in terms of social aid and love.” Whose use? Whose fit? Sigusch, the scholar of Adorno, remains silent. And there it is again: Auschwitz as zeitgeist, as a “watchword of the entire era,” and according to Sigusch, who one would like to certify as deranged, this is also true in “social aid and love.” That is not a Forel quote, but a commentary from Sigusch on Forel's motives. Sigusch then further cites Forel, saying that he saw the “danger of the overgrowth that threatened human cultures through the great fertility of inferior human races,”(377). Sarrazin vobiscum! “Thereby,” Sigusch continues, quoting Forel, “he advised targeting 'especially the Chinese and other Mongols,' but also the 'Negro' and 'eventually' the Jewish race.” But behind this plan, he, “like most sexual researchers,” “had personal integrity?!” Sigusch also cites Forel's list of those worthless lives that should be exterminated by “a painless death,” or the gracious alternative of being forcibly sterilized, and calls it “atrocious” (378). “Among those listed are 'first and foremost all criminals, insane, weak-minded, those with lessened sanity, the wicked, quarrelsome, ethically defective people,' and then later 'drug addicts,' 'those with a hereditary tendency towards tuberculosis, those with bodily sickness, those with rickets, hemophilia, the deformed and others who through inherited sicknesses or sick constitutions are not suitable for the procreation of a healthy human race.'” The haphazard nature of the list of victims mirrors the nature of those to be furthered. Sigusch quotes: “Forel had 'the socially useful people' in view in 1905, who would be 'especially good objects for [eugenic] propagation,' that is, 'those people who enjoy work, have agreeable and steady humors, and are good-natured and accommodating.'” Forel belonged to the steering committee of Hirschfeld's "Weltliga für Sexualreform" (World League for Sexual Reform), a hodgepodge of eugenicists, and writers lacking notable education or trades who were sympathetic to the idea of eugenics – all of whom believed themselves to be the pride of creation. “No wonder,” says Sigusch, “that Hirschfeld continually vied for Forel's favor” and that Kronfeld was allowed to work at a clinic of Forel's son during his exile in Switzerland. It was also no wonder, though Sigusch doesn't mention it, that Hirschfeld followed Forel's ideas exactly in the forward to his 1933 book "Weltreise" (see our depiction above). Sigusch had already keyed his reader to this on page 350: “In today's view the [IfSw] relationship to the eugenic-racial cleansing movement of the time is problematic, which was misunderstood at the time to be forward-thinking and progressive” (emphasis mine). Here one notes again that Sigusch does not have any idea of the reactionary, extreme-right intellectual world of the IfSw participants that we already documented, and which exactly mirrors the extermination fantasies of the self-proclaimed elites against the “masses” of the “mob.” This “relationship” was in no way “problematic” as Sigusch wrote in 2008, but criminal and complicit! And not just “in today's view.” It was already criminal to forcibly sterilize people, or to offer “a painless death” to those whose agency and decision-making ability were taken away through psychiatry, and to clothe these actions in the ideology of eugenics (“good breeding”). Sigusch doesn't problematize the criteria used by these self-proclaimed brilliant people to measure those whom they saw as mere pebbles. Moreover he does not address who determines these criteria (through today, see the German politician Thilo Sarrazin). Sigusch, who was searching for comrades, wants to see the positive in the gruesomeness they caused, because despite everything he feels that be belongs with them. “For me Hirschfeld is not an 'intellectual predecessor of fascism,'” Sigusch writes (386). “I have never asserted that he espoused Nazi or fascist ideas. But even if he had done that, to me he would still not be a 'predecessor' in the sense of a subject who is thinking ahead, as far as that can be isolated epistemologically, because he was far too insignificant a theorist.” The Nazi had merely “used” it. That is not logical or dialectical, that is the logic of the “secrets,” see above. The Setting Power determines who is the Brilliant, and it is the new epistemology not to question that. Sigusch's Hirschfeld apologism is old hat from pre-68 times. One is tempted to feel embarrassed for him. (Moreover, Hirschfeld did not need a theoretical-overhaul, because epistemologically viewed he was a functionalist; Sigusch also misjudges this.) And Sigusch shows Hirschfeld as a Brilliant, politically pragmatic: “Which answers did Magnus Hirschfeld, the great defender of social democratic sexual politics, give? He never contradicted Forel. He called him 'the wisest and best of all modern Europeans' … In the third volume of his 'Geschlechtskunde' (1930 …) Hirschfeld declares himself for the 'weeding out of bad strains of humans,' for raising the people by using forced sterilization and castration.” (378) Is Sigusch crazy? “Hirschfeld was not unscrupulous,” Sigusch writes farther, quoting Hirschfeld, because he worried about the “'large numbers' of those who needed to be managed”, who were suited for extermination. Sigusch also shows in a long quotation from the third volume of Hirschfeld's 1930 Geschlechtskunde exactly whom Hirschfeld believed should fill the mass graves (or crematoriums? or just sterilizing surgeries?), and how Hirschfeld's inexact terminology could have allowed him to put everyone in these categories: “calculations show 250,000 insane, just as many idiots and those with weak intellects, still larger numbers of psychopaths of all kinds. Moreover 90,000 epileptics, 120,000 alcoholics, 18,000 deaf, 36,000 blind, 70,000 recipients of welfare and additionally an army of cripples, vagabonds, prostitutes and criminals (every seventh grown man in Germany is previously convicted.) How heavily the hereditarily burdened portion of the populations weighs on the purse of the state" (it was 1930 – during the Great Depression, don't forget!) "follows from a calculation …" – we'll spare ourselves relating the monetary cost that Hirschfeld calculates “for the care of 33,000 inferior people in Prussia,” and instead quote from Sigusch's book, who relays Hirschfeld's conclusions from Geschlechtskunde: “Such numbers make it understandable that in Germany too the sterilization problem is increasingly drawing the attention of widening circles; on the other side are those who note the tremendous difficulties that would arise from forced sterilization, which actually would markedly relieve the entire body of people from the circles of people who are hereditarily burdened.” Sigusch interprets this passage as if Hirschfeld was growing desperate of his own purposes of breeding a higher race of people. But there are no valid arguments for that point of view. Hirschfeld was a follower of Nietzsche – someone like that does not pause before a difficult task, but rather grows more resolved. You have to understand Hirschfeld's list – from which only escape the Jews (understandably), the Sinti and Roma, Social Democrats, Communists, Bolsheviks, Christians, homosexuals, etc. (except as they were included in Hirschfeld's formulation of “criminals (every seventh man...)”) - as a difficult task. And the Germans were actually undertaking this "task" quite soon ... Indeed before too long, after the government takeover by the Nazis, the racial cleansers and eugenicists addressed Hirschfeld's “tremendous difficulties.” And see: for the Germans it was actually possible to relieve their “entire body of people” of millions and millions of the “inferior” ones by executing Hirschfeld's list and more. And indeed at the beginning they even did so while Hirschfeld believed he should “wait out” the “Hitler experiments” to see what came of them as he wrote down in August 1933 (as Sigusch quoted in his 1985 Spiegel article). Hirschfeld's “doubts” are found almost world-for-word in the Protocol of the Wannsee Conference, the meeting of mid-level German Nazi leadership on January 20, 1942 that is regarded as the deciding event in the murder of the European Jews. There is agreement in the content, and in part even the words, between Hirschfeld's 1930 Geschlechtskunde text and texts from the Conference, and it is astounding and horrifying that until now it has not seemed to occur to anyone except for BIFFF...! Here on one side we have Hirschfeld babbling about “the tremendous difficulties that would arise from forced sterilization, which actually would markedly relieve the entire body of people from the circles of people who are hereditarily burdened,” and Sigusch quoting his idol exoneratively and stating that “Hirschfeld was not unscrupulous.” Meanwhile, State Secretary Wilhelm Stuckart from the Interior Ministry (SS-member number 280 042 and co-author with Hans Globke of the legal commentary on the Nuremberg racial laws) revealed these same “scruples” at the Wansee conference, as the topic of prohibiting “mixing” between “Aryans” and ”Jews” came up (a difficulty for racists that Hirschfeld was familiar with from the USA in terms of white, Asian, and Black people). Stuckart was dubious about the “practical follow-through” of the “correction” of his “Aryan” body of people, because “this would bring with it an unending administration” and called for “proceeding to forced sterilization.” One can read this in the only copy of the protocol of the murder-conference that has yet been found. "Wansee Conference" from 1942

The protocol includes passages that are almost word-for-word the same as part of Hirschfeld's 1930 work Geschlechtskunde:  Above: Excerpt from page 14 of the

Protocol of the Wansee Conference of January 20, 1942, in which the

possibilities of killing the European Jews were debated.

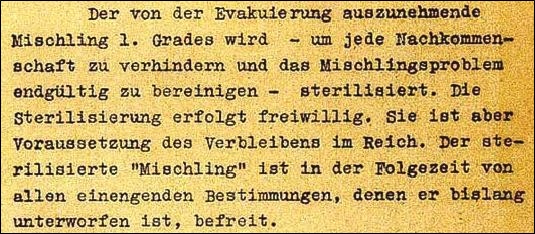

Below: Excerpt from page 11 of the Protocol of the Wansee Conference. The SS-murderer babbles about the “voluntary” sterilization of “mixed” children: “evacuation” was code for deportation into death camps:  The supposed “voluntary” nature of the

sterilization that Hirschfeld advocated for unwished people is still

used by Hirschfeld's fans at the Magnus Hirschfeld Society in Berlin to

exonerate their idol. This despite the fact that Hirschfeld himself, as

Sigusch quotes (see above) actually wrote about “forced sterilization”

in "Geschlechtskunde".

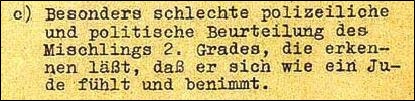

Below: Those who have been in legal trouble, whom Hirschfeld included in his list of the unwanted who should be sterilized (“every seventh grown man in Germany is previously convicted...,”) are also included in the Wansee Conference protocols. People who fail “police judgment” are “equal to the Jews” (part of page 12).  (All BIFFF... screenshots are

from the original Protocol of the Wansee-Conference,

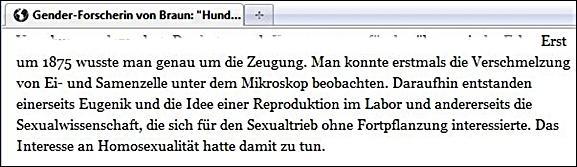

as published by Der Spiegel in PDF form.) Hirschfeld's criticism of the Nazi sterilization-craze, which he published in 1934-1935, was only concerned with the fact that the efforts of the racial cleansers and eugenicists were turned against the Jewish population; he shared a belief in the same principles as the Nazis. In 1935 he even decided that their 1933 eugenics “Gesetz zur Verhinderung erbkranken Nachwuchses" (Law to Hinder Genetically Sick Offspring) was too lax, because it left out the sterilization of Hirschfeld's favorite enemies, the “drug addicts” and “alcoholics.” Sigusch, who does not see the parallels to the Wannsee Conference (or who perhaps does not recognize them or does not want to see them), does allude to Hirschfeld's support for the “Saxon Medical Officer Dr. Gustav Boeters,” one of the most aggressive propagandists for the extermination of people in the Weimar Republic, who taught Hirschfeld about the issue. Sigusch quotes from Hirschfeld's Geschlechtskunde, in which Hirschfeld remarked that Boeters applied to humans the principles “'>that every gardener uses on weeds<'”(380). And Sigusch further alludes to the fact that Hirschfeld is in agreement with Boeters' hatred of “human weeds” and “every freeloader,” and shares Boeters' complaint that “from year to year, taking care of the army of those unworthy for life devours ever-increasing enormous sums.” “Since Auschwitz,” Sigusch now strangely thinks, “every note of animosity against humans must be taken at face value.” But that is wrong, because in 1930 and earlier such a “note” was already criminal and against human rights. Already in the 1920s several IfSw participants based their work on the ideas of the ideas of the philosopher Fries who was an anti-Semite focussed on the extermination of Jews, and Boeters' complaint (quoted by Sigusch in Hirschfeld's Geschlechtskunde), that “parliament and national government” rejected Boeters' suggestions of extermination, shows what the zeitgeist than actually was: the vast majority of the people rejected the anti-humanity politics of Hirschfeld, Boeters, Forel and all of the like-minded people in the "Weltliga für Sexualreform" (World League for Sexual Reform). That also goes for Hirschfeld's few intermittent collaborators in the Socialdemocratic Party SPD, who, unlike Hirschfeld, put aside their eugenics-politics when they couldn't find a majority in their party in the 1920s. Sigusch doesn't say anything about this episode, as he ignores the research and work of all but fans of Hirschfeld. But it was “those who do not participate” (Hannah Arendt), who are the true idols – who were against Hirschfeld and his consorts. To be fair, one must note that Sigusch, despite his attempt to downplay its historical meaning, at least sees the relationship between sexology and racial cleansing/eugenics, which is actually impossible to overlook: racism always begins with sex. Sigusch's fellow Hirschfeld acolyte Christina von Braun, whom he mentions often and glowingly in his Geschichte der Sexualwissenschaft book, sees it entirely otherwise. The filmmaker at the Cultural Institute at the Berlin Humboldt University, who has issued many pronouncements (some say she gossips about everything and everyone), and whose garrulousness has even been mocked in the newspaper Die Welt, denied this connection in an interview with the leading Berlin newspaper Der Tagesspiegel on the occasion of the 100th World Women's Day in 2011 with this synopsis:  (BIFFF...-Screenshot "Tagesspiegel" online March 8, 2011) [translation:] around 1875 for the first

time one could observe the fertilization of an egg with sperm under a

microscope. From this arose on one hand the eugenics and the ideas of

reproduction as a laboratory and on the other hand sexology, which was

interested in sex without reproduction. The interest in homosexuality

had to do with this second strain.

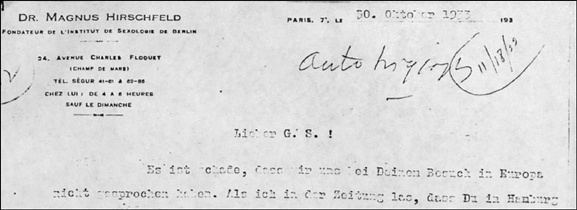

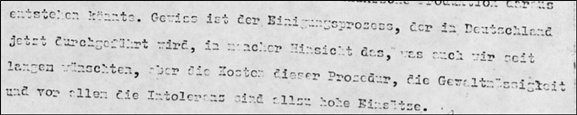

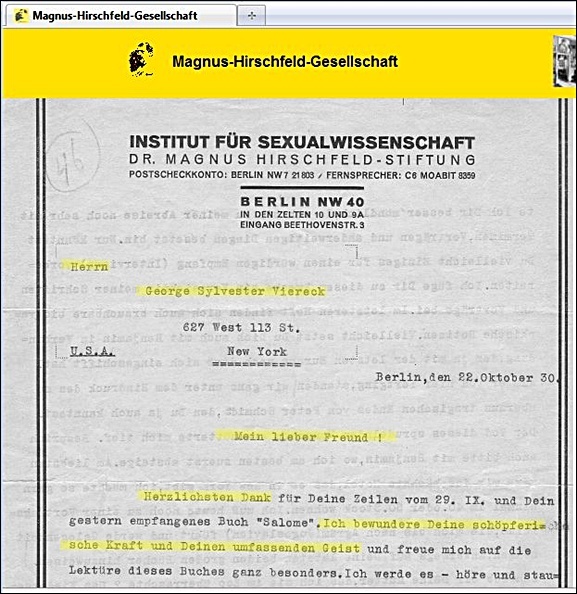

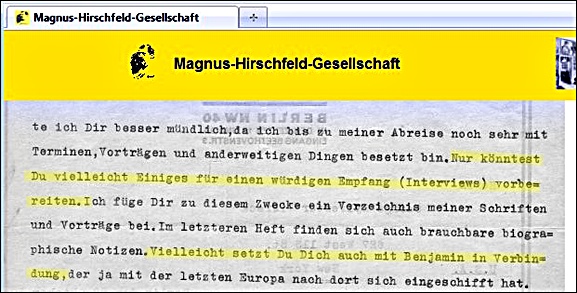

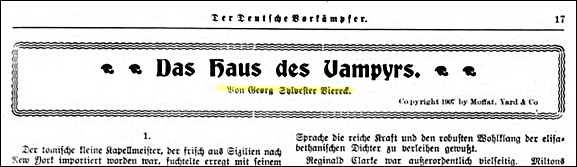

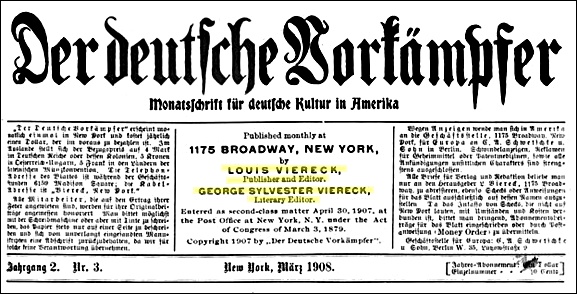

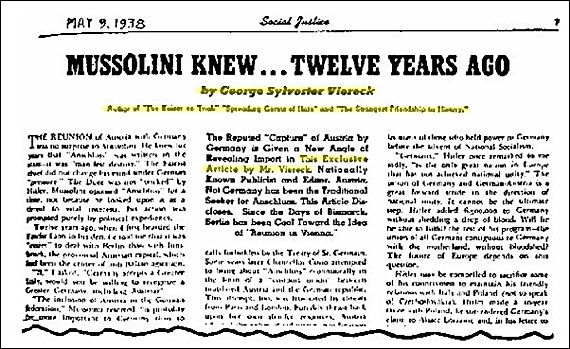

On the one hand, on the other hand, “… had to do with:” yes, it's true that everything in the universe somehow has something to do with everything else, but must Berlin really finance von Braun for this realization? And is it really so hard to understand why the conservatives took the chance to cut funding to Sigusch's Frankfurt Institute after he retired? This kind of sexual science almost hits bottom in Sigusch's depiction of the “destruction of the first Institute for Sexology by the Nazis” in his 2008 history book. His only source is an anonymous “eyewitness” from Willi Münzenberg's extremely homophobic 1933 "Braunbuch über Reichstagsbrand und Hitler-Terror" (Brown Book about the Reichstag Fire and Hitler Terror). Historians of all ideological stripes hold this text as completely unusable as a source. The text is interesting only on a meta level, in relation to the question: What did the exileds in Paris cook up, in an effort to mobilize the up to then sluggish world public opinion against the terrors of the new Hitler regime, a regime whose unabashed terrorism was actually an object of envy to many politicians in other countries? Sigusch continues today to take this understandable and, at the time of its writing, even may be sensible propaganda at face value. He doesn't once discuss the open homophobia of the Braunbuch. Just how wrong he is about this “source” is shown in lines from the Braunbuch about the destruction of the IfSw. The Brounbuch claims that books by George Sylvester Viereck, an open Nazi, self-declared friend of Hitler and also a near friend of Hirschfeld (see below), were taken by Hitler Youth and Storm Trooper leaders out of the IfSw and burned (Sigusch 368). But at the time of the destruction of the IfSw Viereck was already in open service to the Nazis as the propagandist of their politics in the USA (see below). One can even assume that Viereck's name made it into the Braunbuch thanks to Hirschfeld himself. Hirschfeld arrived in Paris on May 14, 1933, where he met Willi Münzenberg, his tenant from 1918, when he lived in a house next to the IfSw that was owned by Hirschfeld. Münzenberg was working on the Braunbuch as the biggest publication attempt by the Paris exiles; the book was published in August 1933. Hirschfeld corresponded at least until October 1933 with his old friend Viereck, whom he hoped would offer him exile in the USA. The motivations were clear: to scare the extreme-right German-friendly circles around Viereck in the hope that they would turn away from Nazi Germany, when they heard that Nazi hordes burned even Viereck's books. But Viereck and his people did the opposite and threw their support fully behind the Nazis; Viereck himself explicitly agreed to a Nazi ban on some of his writings. And nevertheless Hirschfeld refused to break with his old friend (see below). No, Ground Zero of this kind of sexual “science” is finally reached when Sigusch misquotes from a letter that is allegedly from Hirschfeld to Viereck (see below), thus giving him an opportunity to quote himself (which of course is much more important than checking one's sources!): “But 'tragically,' so I said and will continue to say, Hirschfeld 'to the end didn't suspect' the ideas of eugenic extermination – which a letter, written from exile to his friend George Sylvester Viereck on October 30, 1933 and discovered by Atina Grossmann … in the collections of the Kinsey Institute, shows. In this letter he writes: 'Doubtless, the cleansing process that is presently being put through in Germany is in many respects that which we have long wished for, but the costs of these measures, the violence and especially the intolerance, are too high a price to pay for it.'” (emphasis P. K.) Sigusch does not mention who the Nazi Viereck was, although Grossmann (a well regarded historian at the private New York college Cooper Union) introduces him with the words: “Viereck, who was seen as a Nazi-Apologist in the USA,” before she gives the alleged quote. Sigusch just remains silent, and Hirschfeld's incontrovertibly scandalous letter shows (much like the entirely scandalous decades-long friendship between the two men), that Sigusch's words “didn't suspect” hardly describe what was actually going on. Below we further place the letter into its context within Hirschfeld's efforts. The letter, by the way, is typed on Hirschfeld's Paris letterhead and is hand-signed with a signature that doesn't look quite like other Hirschfeld signatures. But in any event, the quote is entirely wrong! A photocopy of the alleged document is in the Haeberle-Hirschfeld Archives for Sexology (HHA) at the University Library at Humboldt University in Berlin. BIFFF...-leader and psychologist Peter Kratz, former lecturer in psychology at the University of Bonn, was, in February 2011, the first who was interested in looking at this photocopy in the HHA, and was the first to recognize its meaning. The real sentence in the HHA photocopy runs: “Doubtless, the unification process that is now being put through in Germany is in some respects that which we too have long wished for, but the costs of these procedures, the violent measures and especially the intolerance, are stakes that are too high.” The deviations from the Grossmann/Sigusch version are considerable; especially politically important is the difference between “cleaning process” [Reinigungsprozess] in the Grossmann/Sigusch version and “unification process” [Einigungsprozess] in the HHA photocopy of the original (if this copy and the original are real, see below.) Hirschfeld's letter

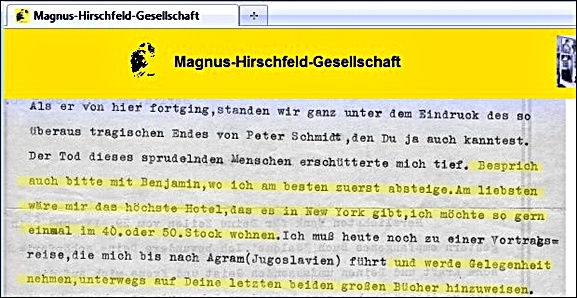

to George Sylvester Viereck (excerpt):

[translation]: "October 30, 1933 … Dear G.S.! It's too bad that we didn't speak during your visit to Europe. When I read in the newspaper that you [had landed] in Hamburg” ...  ... "Certainly, the unification process that is being carried out in Germany in some respects is what we have been longing for, but the cost of this procedure, the violence and above all the intolerance are all too high stakes." ...  ...“Personally I'm doing fine, only my health leaves much to be desired. Dr. M. Hirschfeld.” Pictures above: Screenshot excerpts from a photocopy of a two-paged letter, allegedly from Hirschfeld in Paris to Viereck on October 30, 1933. From the HHA, Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm Center, temporary archive numbers of both photocopied sheets: 128.8-1 and 128.8-2. In the Grossmann/Sigusch version the sentence can be read simply in reference to Hirschfeld's eugenics politics, as Sigusch did: as a cleansing of the body of the people of “weeds,” like a gardener. But in the original, Hirschfeld's statement goes far beyond the narrow boundaries of eugenics (which Hirschfeld doesn't even address in the letter!), about which some would even say today: “Well, 'weeds' is indeed a mean word, but embryo screening, if used properly, is a good thing for parents!” But the national “unification process” of Germany into a total dictatorship points instead to a unified political and societal goal that both old friends openly shared. (Hirschfeld, the one who at the beginning of the 1920s had already been brutally beaten by Hitler Youth on the street, and who especially hated Adolf Hitler as the leading anti-Semite, and Viereck, the Nazi and self-declared friend of Hitler, who at the beginning of the 1920s had already personally interviewed his “Führer,” and who published the interview in his own US newspaper. He then, in 1932, published an edited version in a broschure and in the US newspaper Liberty - in which Hirschfeld, with Viereck's help, had wrtten in 1931 about his eugenics work at IfSw.) Yes, the friends shared the political goal of a “formed society," in which there was just as little room for Marxist class struggle as for the democratic struggle between parties of citizens as for the diverse freedoms of diverse minorities, including the sexual minorities that Hirschfeld and his at one point close co-worker, the psychologist Arthur Kronfeld, held for biologically “degenerate.” Thus viewed, Hirschfeld's connections to the politics of eugenics seem even more dangerous, because it becomes clear how the caprice of Forel's list of those to be exterminated reaches directly into politics and social politics. It's interesting to look at the forgery of the quote from Hirschfeld's letter more closely, because it's a shining example of today's apologist Hirschfeld research and historical writing about Hirschfeld. It is no longer just revisionist history, but rather a broad falsification of history. Sigusch took the quote from Atina Grossmann's lecture “Magnus Hirshfeld, Sexualreform und die Neue Frau: Das Institut für Sexualwissenschaft und dasWeimarer Berlin" (Magnus Hirschfeld, Sexual Reform and the New Woman: The Institute for Sexology and Weimar Berlin,” which she delivered at the conference “Der Sexualreformer Magnus Hirschfeld: Ein Leben im Spannungsfeld von Wissenschaft, Politik und Gesellschaft" (The Sexual Reformer Magnus Hirschfeld: A Life Suspended Between Science, Politics, and Society), which took place in 2003 in Potsdam. It was organized in cooperation between the Moses Mendelssohn Center (MMZ) at the University of Potsdam, the Institute for Cultural History and Theory at Humboldt University, and the Magnus Hirschfeld Society of Berlin. BIFFF... openly criticized the conferece at the time. The talks at the conference were published in a volume, given the same title as the conference, that was edited by Elke-Vera Kotowski and Julius H. Schoeps (both from the MMZ). Sigusch took his quote from this volume (Berlin, 2004, Grossmann's lecture pages 201 – 216). He did not read the original of the alleged Hirschfeld letter to Viereck, and also did not see the photocopy, as BIFFF...-leader Kratz did. We do not know whether Grossmann conducted her lecture in English and used an English text for the book that was then falsely translated back into German by the editors, her coworkers, or the publisher of the conference book. That would be one easy explaination for the errors: Grossmann had translated the Hirschfeld letter from the German original into English, and others translated it back into German without comparing it to the original. In English the difference between unification ("Einigung") and cleansing ("Reinigung") is much bigger than it is in German – they are two entirely different words. The errors would have been apparent. In any event neither the editors Kotowski and Schoeps nor the press took care to proofread the supposed letter against the original. This sort of slipshod research of Hirschfeld apologists is also indicated in footnote 14 of Grossmann's text in the conference book, in which she gives the source of the letter as the “Hirschfeld Collection, Konsey Institute, Bloomington, Indiana.” Yes, that's right, “Konsey Institute” stands there instead of “Kinsey Institute.” So much for the careful academic work of Kotowski and her boss at the MMZ, Schoeps, who for years has written more as an ideologue than a serious historian. At the heart of this kind of Hirschfeld research rests a blatant lie: whatever doesn't fit into the idealogical concept is made to fit. Suspicion is properly directed at Grossmann, whose article (in which the word apologist is not strong enough to describe her admiration for Hirschfeld) also alludes to her family connections with Hirschfeld (203). Still more: Grossmann invents that Hirschfeld wrote the unification/“cleaning” quotation “in response to the sterilization law of the Nazis in 1933” (205). But there is no mention of eugenics or this Nazi law in the letter (see the entire text of the letter). The quote has much more to do with Hirschfeld's remark that his friend Viereck, as expected, had succumbed to “the Hitler suggestion.” Thus the thought process of the letter taken as a whole matches exactly our interpretation (see above). And here the question arises whether Grossmann, whose forgery has now been, with Sigusch's help, preserved in the literature, has ever even seen the letter, to say nothing of “discovering” it, as Sigusch claims that she did. The editors of the conference reader, Kotowski and Schoeps, gave no thought to that. But we are again vindicated in our critique of the conference (at which, by the way, Christina von Braun again had something to say, and indeed something that was almost word-for-word the same as she said in the Tagesspiegel interview eight years earlier) as well as our critique of the resulting book. A book that today is in almost every gay bookstore, in an effort to have something serious about the history of the movement next to the porn. We at BIFFF... are not only the first ones to look at the photocopy of the original letter and prove that the quote was wrong, but also the first ones to question the overall authenticity of the letter. Grossmann claims that the Hirschfeld material at the Kinsey Institute, which HHA founder Erwin J. Haberle obviously drew on - he worked there for a long time in the 1980s, comes from Hirschfeld's friend Harry Benjamin, who preserved it for decades and then gave it over to the Institute (206). Benjamin is certainly one of our unreliable sources: nature-apostle and psycho-esoteric in the tradition of Gurdijeff, he worked as a resident physician in New York and San Francisco, conducted hormone experiments in an attempt to cure homosexuality, wrote about this and that and was hardly a great light of science, even if interested circles today credit him with the “discovery” of transsexualism. These are the same circles, by the way, in which the Hirschfeld apologists are found. How did Benjamin come to have a letter that Hirschfeld sent to Viereck? Benjamin could have falsified this letter in order to make himself, as a friend of Hirschfeld, important- and interesting-seeming, for example to Alfred Kinsey, with whom Benjamin became acquainted long after Hirschfeld's death. The letter is typed, and says that it's from Paris, but it has German umlauts in it. On a French typewriter? Maybe at the end of Hirschfeld's world travels, when he was in Austria or Switzerland (in 1932! And not, as J. Edgar Bauer wrongly states on page 271 of the Kotowski/Schoeps reader: “Hirschfeld's trip, which took place between November 1930 and April 1931;” the error is also on the HU-HHA website, which reprinted this text from Bauer – the apologists never get it right! In his text “Adam's Death,” which originally was published by Manfred Herzer in the collection of lectures 100 Jahre Schwulenbewegung (100 Years of the Gay Rights Movement) and is also – as a “revised edition”! - on the HHA website, Bauer even claims that Hirschfeld first started his journey to America in 1931: “1931, as he went to America,” – one can't believe that such people are taken as the legitimate interpreters of the “Hirschfeld œuvre!” (Bauer) Still more: Herzer himself, up to now the only German-language biographer of Hirschfeld, wrote in September 2011 in his unspeakably error-filled article Magnus Hirschfeld Lehre von den sexuellen Zwischenstufen und der Historische Materialismus (Magnus Hirschfeld's Doctrine of Intermediate Stages in Sexuality and Historical Materialism) in Volume 293 of the formerly Marxist publication Das Argument, that Hirschfeld traveled to the USA in 1931: “At the beginning of 1931, shortly before he left Germany, which was increasingly broken by Nazi terrors...” (566)! In his Hirschfeld biography's, “second, revised edition” in 2001, Herzer wrote correctly “November 1930.” What should one do with an Argument magazine, in which in the first paragraph of the first article from the first and only Hirschfeld-biographer such a central date in Hirschfeld's life is wrong? Throw it in the trash and cancel the subscription!) – To begin again: Maybe at the end of Hirschfeld's world travels, when he was in Austria or Switzerland in 1932 (!) he bought a typewriter with German letters in order to write his Weltreise World Journeys, and he brought it with him to Paris. The Hirschfeld signature on the Viereck letter is unusual compared to others. Maybe there is no original at all, and the example that Grossmann is supposed to have found in the Kinsey-Institute is also just a photocopy, maybe one patched together by Benjamin. Who will go there and look? Benjamin and Viereck were acquainted with each other and had contact with each other in New York, arranged by Hirschfeld. At the point of this letter Viereck was already in the service of the Nazi regime, and Benjamin was of Jewish heritage. But Benjamin in his eighties still referred to Viereck as “our mutual friend” (see below). There are evidently no more extant letters from Viereck to Hirschfeld, because there are none listed in the US archive where Viereck's correspondence is kept, and none were presented to us at the HHA. Hirschfeld's letter to Viereck on October 30, 1933 is still the last verifiable contact between the two (that is, if it is real). But who knows what may yet be found in the autograph market of US antique stores! Perhaps Benjamin was not the source of the Kinsey Institute, as Grossmann, who never critically investigated the letter, believes, but rather Viereck himself. Because there is proof in US archives of correspondence between Alfred Kinsey and Viereck. A critical examination of the Hirschfeld scene comes up against such ponderable and imponderable questions again and again. The apologists simply turn away. Let's presume that the text is real. The original version with the “unification process” of the German people, which was finally “put through” in 1933, shows the continuity of Hirschfeld's thoughts: his wild celebration of the beginning of World War I as a unifications process of the Germans in a people's war against the French, which Sigusch explicitly quoted and critiqued in his Spiegel article in 1985 (see above), is a little bit more measured in October 1933. Hirschfeld at this point was older and not in good health – so one doesn't shout “Hurray!” quite as loudly as in 1914, when Hirschfeld quoted Goethe, saying “'How everything weaves itself into the whole, One in the other works and lives!'” The German “war Socialism,” out of which fascism and National Socialism developed as communal ideologies of national and economic forms (and in which Lenin, astoundingly, saw a model for the Soviet planned economy!) was always Hirschfeld's political goal: the “social eugenics” within the SPD were part of this, as well as Hirschfeld's contacts with the Noske-faction of the SPD. Hirschfeld's idea of the “people's community as a homogeneous body of people” from his plan for the “nationalization of health care” in 1919 fit in with this idea, as well as the goal that this plan should serve: “Germany [...], which from the hard calamities of these days will rise up to new fortune and new strength.” Sigusch missed his chance to understand this continuity through his unverified misquote. The circle around Hirschfeld assembled in these anti-democratic and anti-liberal forms of society, a circle that overlapped with the circle around the authoritarian ideologue Leonard Nelson, Kronfeld's idol, as our study “From Antisemitism to Homophobia” proved. It also overlapped with the ideas of the Nelson circle's "Internationaler Sozialistischer Kampfbund ISK" (International Socialist Combat League) and their newspaper Der Funke, which in 1932-1933 fought against the “false” leader of the Nazis and fought for the supposedly “right” leader of the Nelsonites – and both were against the pluralistic Weimar democracy. The Frankfurter Allgemeine FAZ newspaper has just reminded readers of the parallels in Spain under Franco's fascism, where a political eugenics developed against left-wingers and democrats. This eugenics espoused the biological and medical “unworthiness” of those who fought for human emancipation in the tradition of the French and American revolutions and Marxism. This was based on the work of the German biological constitution-psychiatrist Ernst Kretschmer, a Nazi and supportive member of the SS, who as the “judge of the court of hereditary heath” made decisions about forced sterilization, who was directly involved with euthanasia actions, and who, according to Sigusch (who remains silent on all of Kretschmer's connections with the Nazi crimes) was “friends” with Kronfeld (359).  (BIFFF... screenshot, FAZ online, March 9, 2011, from the article by Paul Ingendaay, “Stealing Children in Spain, Eugenics under Franco). We claim that Hirschfeld was sympathetic to the pro-fascist (Noske) wings of the Social Democrats and in many instances (not only in his worship of Nietzsche and Haeckel) stood closer to the “Konservative Revolution" (conservative revolution, "Alt Right" in nowadays) than the Weimar democracy, that he had in mind a fascist-planned “modern” society and in no way the West-oriented left-liberal guarantee of individual freedom and the equal treatment of each individual before the law. This claim is supported not only through the correction version of his quote regarding national unity, but is also borne out by an investigation of his dealings with fascist and fascist-influenced friends in the USA, which whom Viereck brought his old friend Hirschfeld in contact. One should never forget that large parts of the original fascist movement lacked the antisemitic factor. The Nazi Viereck organized Hirschfeld's USA trip Hirschfeld's world travels began in November 1930 with his departure for New York. His book about those travels, Weltreise eines Sexualforschers im Jahr 1931/1932 (World Journeys of a Sexual Researcher in the Years 1931/1932), begins with his trip away from San Francisco in March of 1931. The book was published in Zürich in 1933 and today is available for purchase in a new edition. His time in the USA from November 1930 through March 1931 has been until now mostly unknown and unresearched, despite the fact that he seems to have planned his further travels to Asia and the continuation around the world while he was in the USA. BIFFF... is the first to shed some light in this darkness with the first publication about Hirschfeld's statements and articles from this trip, and will publish excerpts of these articles with commentary. With the help of the German-American extreme-right writer and politician George Sylvester Viereck these articles of Hirschfeld appeared in US newspapers and periodicals that belonged to the Hearst corporation, Viereck's occasional employer. It emerges from these articles that Hirschfeld attempted to propagate his views on eugenics in the USA because he hoped for greater resonance there. He had reason to hope for this because in some American states there had come already eugenic laws about sterilization and forced sterilization of people who were defined as “disabled” into force; there were also legal prohibitions of marriage between whites and blacks or Asians. These laws were justified either using the veiled language of eugenics or in some cases, open racism. Hirschfeld even opens the first chapter of his Weltreise book with the fact that he was seen off in San Francisco by the city's German Consul General. That was Werner Otto von Hentig, at that point already a known agent of the “national revolutionaries” in the “conservative revolution” in Germany. (That term was coined by Armin Mohler in his 1950 book, which offered an overview of the extreme-right anti-democratic strains that more or less quickly and completely flowed into National Socialism. The "Alt Right" of today refers to this.) (Werner Otto von Hentig was also the father of the well-known modern pedagogue Hartmut von Hentig.) Hirschfeld writes in a style that indicates how well he thinks of himself, noting that “23 people accompanied me on board, among whom was the German Consul General Hentig – known for his bold riding during the World War from Kabul in Afghanistan to the Chinese coast. He brought a parting gift for me of some books he had published and gave me his thanks for what I had done for Germany's reputation in America, as an advocate of German science.” The diplomat von Hentig, an adventurer and a shifty character, had tried during the First World War to foment rebellion among tribal chiefs in Central Asia against British colonial rule, which the German Empire thought would weaken the British and offer Germany advantages in the European war. Hirschfeld and his colleagues were at the same time excited devotees of the German war policies and German Kaiser Wilhelm II, while Viereck advocated for these politics in the USA (see below). Hentig, who received the order of the “Cross of the Knight with the Swords of the Kingly Order of the House of the Hohenzollern” from the hand of Wilhelm II, left the diplomatic service off and on and was active with his brother Hans von Hentig in the German resistance to the beginning of the Weimar Republic against the republic. (His brother was also a national revolutionary of the first post-war hours, and wrote the book Das Deutsche Manifest The German Manifest. He then was an eugenic criminologist and advocate for racial cleansing, who held “Negroes” for especially biologically inclined towards criminality. After 1945 he fought for the “criminalization” of homosexuals.) In 1923-1924 the brothers were involved in the Thuringian communist uprising; at that point the KPD believed that it could ally itself with the “war Socialist” groups in the Weimar armed forces and the Noske-faction of the SPD, and military units held maneuvers in the Soviet Union, which was against the Treaty of Versailles. Later Werner Otto von Hentig became a close friend of the Nazi-dissenter Otto Strasser, who at the beginning of the 1920s moved from the SPD to the Nazis, developed his own version of a “German Socialism” (Prussian fascism) and left the Nazis in 1930 due to the pro-capitalist policies of the Hitler-Göring majority faction. Returning to the foreign office, Werner Otto von Hentig led the Orient Division and was the Nazi contact person to Mohammed al-Husseini, the “Grand Mufti of Jerusalem,” a Hitler-fan and tireless helper of the effort to exterminate European Jews. During World War II Husseini aspired to expand that extermination to Middle Eastern, and especially “Palestinian” Jews of the Zionist settlement movement, with the help of Expeditionary Corps from the Wehrmacht. In April 1945 Hentig personally helped Husseini, the most important connection between the extermination antisemitism of the Nazis and the Islamic antisemitism of the Middle East, flee from Berlin (where he had lived since 1941) to Switzerland. On April 28, 2010 the Süddeutsche Zeitung wrote that Hentig had championed the idea of publishing an Arabic translation of Hitler's Mein Kampf. He believed that its distribution would generate wide-reading sympathy in the Arab world, and that it would be of great propagandistic worth to Hitler Germany. Hentig received numerous Nazi Orders, including the “Romanian Remembrance Medal 'Crusade against Communism'” in 1943, and was graded as a “chief culprit” during de-nazification proceedings. After a break Hentig again appeared in the diplomatic service of the foreign office in the 1950s, now for the Federal Republic of Germany, and made a name for himself as an opponent of Adenauer's policies of integration with the West. He kept in close touch with Nazis in hiding in Arab states. In the 1960s von Hentig, Wolf Schenke and other former Nazis formed extreme-right “neutral” political small groups that worked against Germany's entrance into NATO. Schenke was previously a functionary of the national leadership of the Hitler Youth, who worked at the Nazi Party Paper Völkischer Beobachter. He was the agent of Nazi Germany in Japanese-occupied Shanghai (one of the main sanctuaries for exiled European Jews, whom Schenke rooted out. For this he was brought before a war tribunal after the war by the USA, but was acquitted). Hentig also wrote anti-Israel articles in Schenke's paper Neue Politik, in which Otto Strasser also published. (More about this scene on this BIFFF…-website, just use the search function at the beginning of the entry side.) One has to know something about Werner Otto von Hentig and his politics in order to truly read and understand Hirschfeld's Weltreise book. Certainly one can not hold Magnus Hirschfeld, who died in exile in France in 1935, responsible for the development of his acquaintances and friends in the following decades. This warning will become even more important in our accounts below. But it will also become clear that the political person Hirschfeld, who in the 1910s and 1920s was involved with many politicians, who made political demands and who helped write bills, was hardly unknowing and naive in 1931 about the anti-democratic national revolutionaries in service of the Weimar Republic that Werner Otto von Hentig had approached. Hirschfeld's mention of Hentig's oh-so-heroic “ride” in World War I, which served anti-British uprisings and the German war goals, and which von Hentig had portrayed in his book Von Kabul nach Shanghai (From Kabul to Shanghai), proves this. It can also be surmised, in the context of von Hentig's remark that his guest Hirschfeld was the “advocate of German science in America” (relayed proudly by Hirschfeld), that Hirschfeld and von Hentig had talked in San Francisco about the eugenic racial-cleansing criminology work of Hentig's brother Hans, which had been published in Germany at around that time, and was a topic of mutual interest and small talk. They knew each other, they knew about each other, they each praised the other. At least that. One can say that, without doing Hirschfeld an injustice. The question arises whether and how Hirschfeld profited from Hentig's old Shanghai contacts during his trip to China; if Hentig opened doors for him there. But it is already clear that Hirschfeld profited from his sojourn in the USA. In the same statement from August 1933, in which he called for patience with the “Hitler experiments” and which Sigusch published verbatim and complete (see above), Hirschfeld admits to having learned “in California” that the human “trials” that took place there had given “in most cases a favorable result for sterilization” (385). (Once again, the authenticity of these words are called into question in the new edition of Sigusch, because it becomes clear that it was just taken from an unknown person's gossip about a “conversation” that Hirschfeld is said to have had with another unknown person.) But then, Hirschfeld himself uttered doubts about eugenics because of the many open questions about the inheritance of human characteristics. Seizing word-for-word an argument of the neurologist and Hirschfeld-critic Albert Moll, Hirschfeld said “It suffices to think about Beethoven alone, whose father was an alcoholic. One must wait out Hitler's experiments, before one speaks out about them. Not only for scientific reasons. Because it's in no way sure that the National Socialists are acting purely for purposes of eugenics. One has greater reason to fear that they use sterilization less in order to 'breed the race higher,' and more in order to exterminate their enemies. The events of the last months offer enough indications to ground such fears.” Stick that you have been, Once again stand still! (Goethe, The Sorcerer's Apprentice) Hirschfeld had known what was going on at least since the early 1920s, when he was attacked on a public street by Nazis. Why then this “waiting out?” The man was simply unteachable, like the sorcerer's apprentice. And the masters of the sorcery, the “secrets” of the “high powers,” were the “masters from Germany” as Goethe would never have dreamed: more faustian than Faust himself. And no sissy could stop them. In the same year, 1933, Hirschfeld again rested his hopes on eugenics (see above) in the forward to his Weltreise book. At the end of the year he wrote the lines to Viereck (see above), that the “unification” of his beloved Germany, which the Nazis were then executing, was also his goal, only less brutal: “painless death” like Forel, but dead still. We have the very dubious Magnus Hirschfeld Gesellschaft (MHG) and its partly dubious funders like the author Marita Keilson-Lauritz to thank for the fact that a letter from Hirschfeld to Viereck from October 22, 1930 was purchased in “a US antiquities shop,” as the MHG writes. The letter, evidently from the Viereck estate, which had been partially sold off in the US, was published on the MHG website in December 2005. In it, Hirschfeld asks Viereck to organize his trip to America and to prepare for him a “worthy welcome” in New York. It is the tragedy of all of the MHG backers that because of this letter, Hirschfeld's connections to prominent US right-wing extremists, which he had already cultivated in the 1910s and 1920s from and in Berlin, became better known. Hirschfeld's “sexual science” and politics must now be categorized in a way that runs counter to the efforts of the MHG to idealize their hero. It may be doubted whether the MHG understood the weight of their decision to put the letter on the Internet. The name George Sylvester Viereck alone, a German-American extreme right-wing writer and politician whose decades-long close friendship to Hirschfeld had until this point played no role in research into Hirschfeld, destroys more than twenty years of work of Hirschfeld apologists trying to polish the legacy of their idol. That Hirschfeld's US trip was entirely dependent on Viereck's support shows how close the friendship between the two was. It certainly was closer than Hirschfeld's friendship with Harry Benjamin, his colleague in the sexual sciences. Benjamin was a member of the International Committee of Hirschfeld's World League for Sexual Reform and served as the organization's North American proxy. Benjamin also offered his support for Hirschfeld's arrival in New York. Hirschfeld asked Viereck in the MHG letter if he would like to get in contact with Benjamin about the “worthy reception.” A letter from Hirschfeld to Benjamin from October 14, 1930, whose photocopy can be found in the HHA shows that Hirschfeld used the formal form of “you” with Benjamin (Archive-Nr: 0561-2). In the MHG letter to Viereck (a contemporary of Benjamin) he uses the informal version of “you.” Copies of other letters to Viereck in the HHA also show Hirschfeld using the informal pronoun. That did not change after their time in New York, because in a letter to Benjamin from San Francisco on February 25, 1931, whose photocopy is also in the HHA, he continues to use the formal “you” (assuming that all these photocopies with their varying signatures are real.) The meaning of the Hirschfeld-Viereck relationship has never been a subject of research, despite the fact that Viereck visited Hirschfeld whenever he made one of his frequent European trips in the 1910s and 1920s, and despite the fact that at the end of 1933 Hirschfeld still hoped that Viereck would help him come to the United States in exile (see below). In the well known Hirschfeld biography by Manfred Herzer (and it is well known despite being unspeakably bad, full of holes, and often entirely wrong), Viereck, Hirschfeld's long-time and important friend, is not even mentioned! (Magnus Hirschfeld: Leben und Werk eines jüdischenschwulen und sozialistischen Sexologen, Life and Work of a Jewish, Gay and Socialist Sexologist, 2nd revised edition, Hamburg 2001) Besides BIFFF..., which by 2008 had already suggested the meaning of this relationship to the assessment of Hirschfeld's sexual politics, none of the (apologist) Hirschfeld researchers seemed to be interested. In the last decade the research surrounding this much-lauded “sexologist” seems to have ground to a halt. Even the 2003 conference didn't bring any really new discoveries, but just served to preserve a monument. After we began to illuminate the political background and ideology of the IfSw founders in 2003, with the publication of a work about Hirschfeld's close coworker Arthur Kronfeld, there was only the publication of the Hirschfeld-Viereck letter by the MHG as a new discovery in the whole Hirschfeld topic. Only we recognized its importance. The MHG even published current photos of Viereck's old house on their website, but only gave a few hints about Viereck the person. This despite the fact that in his letter Hirschfeld promised to advertise Viereck's books at his lectures. Also the Viereck and Hirschfeld contents of the HHA archives had not yet been reappraised, certainly not in light of their political importance. And once again it is we at BIFFF... who for the very first time take a look at these archives. When one examines the material in the archives and Hirschfeld's articles from America in 1930-1931 which Viereck published and we braught to Europe first to publish them one by one commented critically, a view of Hirschfeld appears that makes it easy to guess why the apologists have never applied themselves to these newspaper documents, even though they have always been available. Quotes from the

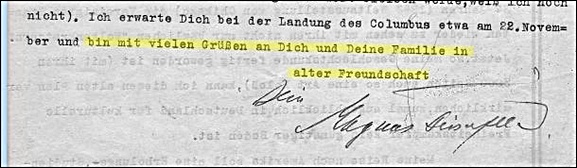

Hirschfeld-Viereck letter of the MHG: